Proxy Infrastructure as a System: Lessons from Recent Network-Level Disruptions

Proxy networks are distributed systems, yet they are rarely engineered with the same rigor as critical application stacks. We analyze the architectural flaws behind recent industry-wide disruptions and outline how Swiftproxy builds for long-term operability by decentralizing control planes and enforcing strict traffic segmentation.

Recent large-scale disruptions in proxy-related infrastructure have sparked intense discussion across the web data and security communities. While public narratives often focus on external enforcement or malicious campaigns, those explanations only scratch the surface.

From an engineering perspective, the more critical question is: What system-level design decisions allow proxy infrastructure to fail suddenly and completely?

At Swiftproxy, we look at proxy networks not merely as services, but as complex distributed systems. In this article, we examine where architectural risk tends to accumulate and how to build for long-term operability.

Proxy Networks Are Distributed Systems

At scale, a proxy network behaves exactly like any other distributed system. It is characterized by:

- Massive Node Density: Thousands to millions of heterogeneous nodes.

- Shared Planes: Interconnected routing and control planes.

- Mixed Trust Levels: Workloads ranging from legitimate research to adversarial behavior.

- Fragile Dependencies: Heavy reliance on external DNS, cloud providers, ISPs, and browser environments.

Failures in these systems rarely originate from a single "bad day." Instead, they emerge from coupled assumptions that were never stress-tested against catastrophic conditions.

Three Architectural Pressure Points

Based on recent industry analysis, three specific design flaws appear repeatedly during infrastructure collapses.

1. Control-Plane Centralization

Many networks centralize authority into a narrow set of domains or routing endpoints. From a systems perspective, this creates a binary failure mode:

- High Blast Radius: A single disruption affects the entire user base simultaneously.

- Limited Fault Isolation: No "bulkheading" to prevent one region’s failure from cascading.

- External Fragility: Hard dependencies on specific registrars or DNS providers.

Engineering Takeaway: A resilient network must assume that control-plane access will be challenged. Architecture should favor decentralized routing nodes that can function even if the primary dashboard is unreachable.

2. Weak Trust Boundaries Between Traffic Classes

Proxy traffic is inherently heterogeneous, yet many providers mix "Data Collection" with "High-Risk Automation" on the same back-end infrastructure.

- Emergent Risk: Without strict segmentation, legitimate enterprise workloads inherit the IP reputation and legal consequences of unrelated abuse patterns.

Engineering Takeaway: Trust boundaries must be explicit, enforced, and observable. At Swiftproxy, we believe "clean" traffic should never share a routing path with unverified or high-risk activity.

3. Reactive vs. Runtime Abuse Detection

In many networks, abuse detection is a policy layer rather than a system requirement. Action is only taken after external pressure (like a platform block) appears.

- The Missing Loop: Without continuous signals—such as anomaly detection and behavioral thresholds—the system cannot self-correct in real-time.

Engineering Takeaway: Abuse prevention is a runtime requirement. A system that cannot detect its own misuse is a system waiting to be de-platformed.

Why "Availability" Is an Incomplete Metric

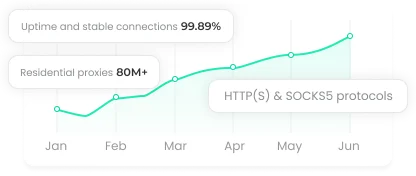

Historically, proxy services have been judged on raw IP counts, geographic coverage, and cost. However, these metrics only describe performance under normal conditions. They say nothing about behavior under stress—regulatory shifts, platform enforcement, or coordinated infrastructure takedowns.

A more useful engineering lens is: Does this system fail gracefully, or does it fail catastrophically?

Designing for Long-Running Operations

At Swiftproxy, proxy infrastructure is treated as part of the application stack—not an external convenience.

That assumption drives several design priorities:

- Minimizing single points of failure in control and routing layers

- Enforcing separation between traffic categories at the infrastructure level

- Continuous monitoring to detect abuse before it propagates

- Favoring predictable, governed growth over uncontrolled scale

These choices are less visible than raw IP counts but they matter when systems are expected to run continuously, not opportunistically.

An Industry-Level Maturity Shift

What we are seeing is not a one-off failure, but a maturity transition.

As proxy usage moves deeper into production systems, expectations shift accordingly:

- From access to assurance

- From volume to governance

- From short-term availability to long-term operability

Distributed systems that cannot tolerate scrutiny are not production-ready systems; proxy infrastructure is no exception.

A single bad decision rarely causes sudden infrastructure collapse. It is the result of many reasonable assumptions compounding over time.

For engineering teams building on proxies, the lesson is clear: Treat proxy networks like critical infrastructure—because functionally, they already are.